By Worshipful Brother Alex Lehning of Washington Lodge No. 3 in Williston, Vermont

Most Freemasons, and Freemasonry as a whole, are particularly mindful of our heritage. Both the most experienced Master Mason and the newest Entered Apprentice can appreciate the lessons and knowledge available to us through careful study.

Our reverence for the wisdom of the liberal arts and sciences provides us with a unique perspective on the architectural foundations and columns of the built world, as well as a healthy respect for mathematical numbers and letters. In addition, we see, as others do not, the internal beauty of the natural world, from the grandeur of the sun, stars, and moon, to the sacred and solemn symbolism of the most modest acacia tree. To be a Mason is to be in possession of a special gift, to always be in search of meaning, present or hidden, in the world around us.

The “forget-me-not,” is the informal name of the Myosotis flower, generally known for being small, with 5 blue petals. Historically, it holds a place in the poetry of Wadsworth and Thoreau, medieval German legends, Christian hagiography(biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader), and English political history.

For Freemasons, the forget-me-not is a symbol that reminds us of resilience and resistance, and of love for the Fraternity and its principles, even under distress and persecution.

From its inception in 1933, Nazi Germany placed a strong emphasis on propaganda and achieving a positive public perception of its ideological goals. This included legal, political, and civic restrictions against opponents of the regime, and those who were victims of its rigid racial and social ideology. Along with Jews, homosexuals, those living with physical and mental handicaps, Catholics, and Jehovah’s Witnesses – Freemasons were targeted for criminal prosecution and exclusion from society. This was achieved in a number of ways.

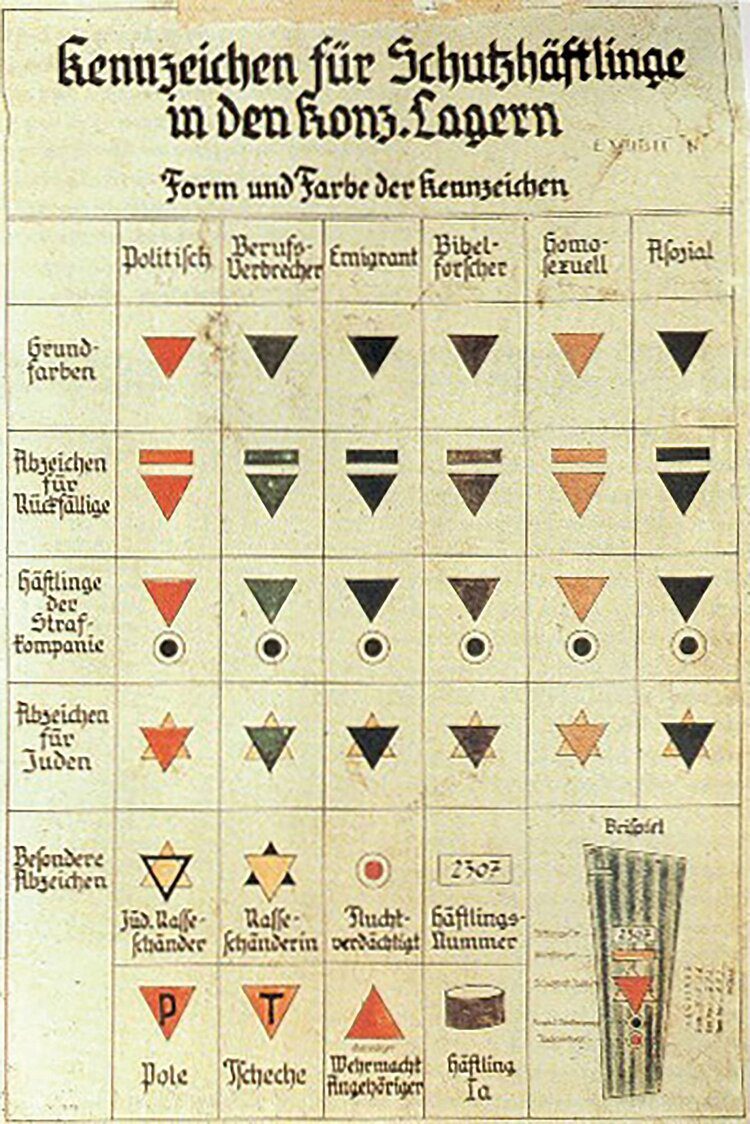

The Enabling Act of 1933 allowed for a governmental decree the following year that officially dissolved all Masonic Lodges within the Third Reich, confiscated their property, and formally barred those associated with Freemasonry from membership in the Nazi Party. In 1934-and 1935, the Ministry of Defense ruled that soldiers, officers, and civilian personnel could not be members of Masonic organizations, and Hitler declared a victory over “international Jewry” in which he linked antisemitism to conspiracy theories about Freemasonry. Freemasons were considered political prisoners within the German concentration camp system, and thus forced to wear the inverted red triangle badge.

Just as Jews were forced to identify themselves with yellow stars, gay men in concentration camps had to wear a large pink triangle. (Brown triangles were used for Romani people, red for political prisoners, green for criminals, blue for immigrants, purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses and black for “asocial” people, including prostitutes and lesbians.)

Just as Jews were forced to identify themselves with yellow stars, gay men in concentration camps had to wear a large pink triangle. (Brown triangles were used for Romani people, red for political prisoners, green for criminals, blue for immigrants, purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses and black for “asocial” people, including prostitutes and lesbians.)

The head of the “SD” Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service), the intelligence branch of the “SS”(Schutzstaffel, Protection Squadron), Reinhard Heydrich, labeled Masons as “most implacable enemies of the German race.” He later demanded that Germany “root out from every German the “indirect influence of the Jewish spirit” — “a Jewish, liberal, and Masonic infectious residue that remains in the unconscious of many, above all in the academic and intellectual world.”

The SS featured two separate offices dedicated to pursuing Masonic properties and Freemasons, a process that would continue into the war and into countries under direct or indirect German control. Vichy France declared Freemasons ‘enemies of the state’ and in Fascist Italy, Mussolini spoke out against Jewish-Bolshevik-Masonic conspiracies.

Anti-Freemasonry took many forms under the Nazis, both individual and collective, and in official and informal capacities. The most popular charges were conspiratorial and antisemitic. That is, Freemasonry was linked to a variety of Nazi enemies to Communism, the international press, and Jews. This was done in Party newspapers and literature, in political speeches, and through indoctrination events such as museum exhibitions.

For example, mock lodge displays were set up featuring skeletons in Masonic regalia alongside Jewish symbols or imposing the square and compass over or alongside a six-pointed Star of David. Portraits of prominent Freemasons were displayed alongside a Torah scroll, and posters featuring the site of European radical political revolutions featured a Masonic apron.

Free association between and among Masons under Nazi control was dangerous. There were Brothers, however, who were determined not to give up their identity as Freemasons, even under these most difficult of circumstances. For example, at the concentration and later prison camp at Esterwegen, Belgian political prisoners formed the Loge Liberte cherie (Beloved Liberty Lodge) and conducted meetings and ritual in secret from 1943-1944.

In 1926, the Grand Lodge of Germany held its annual meeting in Bremen in northern Germany. It adopted a blue forget-me-not badge as its emblem, which was produced by a local factory. By coincidence, the same facility was called upon to produce a blue forget-me-not lapel pin in 1938 by the National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization, to commemorate its Winterhilfswerk, or winter charitable contribution drive. The pin was a gift to donors. Thus, the blue forget-me-not, ostensibly a symbol of Nazi social policy, became a symbol of Freemasonry a clandestine badge of membership.

This article was provided by Worshipful Brother Alex Lehning of Washington Lodge No. 3 in Williston, Vermont

The following discussion and additional facts are provided by:

The “Forget Me Not” Pin and Freemasonry

The following is taken from a presentation card issued by the American Canadian Grand Lodge, AF&AM within the United Grand Lodges of Germany. Submitted By Wade A. Huffman (Light of the Three Stars Lodge #936 AF&AM, Ansbach, Germany and Lancaster Lodge #57 F&AM, Lancaster, Ohio).

The Forget-Me-Not (Das Vergissmeinnicht)

The Story Behind This Beloved Emblem Of The Craft in Germany

In early 1934, soon after Hitler’s rise to power, it became evident that Freemasonry was in danger. In that same year, the “Grand Lodge of the Sun” (one of the pre-war German Grand Lodges, located in Bayreuth) realizing the grave dangers involved, adopted the little blue Forget-Me-Not flower as a substitute for the traditional square and compasses. It was felt the flower would provide brethren with an outward means of identification while lessening the risk of possible recognition in public by the Nazis, who were engaged in wholesale confiscation of all Masonic Lodge properties. Freemasonry went undercover, and this delicate flower assumed its role as a symbol of Masonry surviving throughout the reign of darkness.

During the ensuing decade of Nazi power a little blue Forget-Me-Not flower worn in a Brother’s lapel served as

one method whereby brethren could identify each other in public, and in cities and concentration camps throughout Europe. The Forget-Me-Not distinguished the lapels of countless brethren who staunchly refused to

allow the symbolic Light of Masonry to be completely extinguished.

When the ‘Grand Lodge of the Sun’ was reopened in Bayreuth in 1947, by Past Grand Master Beyer, a little pin in the shape of a Forget-Me-Not was officially adopted as the emblem of that first annual convention of the

brethren who had survived the bitter years of semi-darkness to rekindle the Masonic Light.

At the first Annual Convent of the new United Grand Lodge of Germany AF&AM (VGLvD), in 1948, the pin was

adopted as an official Masonic emblem in honor of the thousands of valiant Brethren who carried on their

masonic work under adverse conditions. The following year, each delegate to the Conference of Grand Masters in Washington, D.C., received one from Dr. Theodor Vogel, Grand Master of the VGLvD.

Thus did a simple flower blossom forth into a symbol of the fraternity, and become perhaps the most widely

worn emblem among Freemasons in Germany; a pin presented ceremoniously to newly-made Masons in most of the Lodges of the American-Canadian Grand Lodge, AF&AM within the United Grand Lodges of Germany. In the years since adoption, its significance world-wide has been attested to by the tens of thousands of brethren who now display it with meaningful pride.

![]()

What follows is another view – written by a Brother Mason

The origin of the information is an article in TAU 2/95 p.95f (the German Quatuor Coronati periodical), a “letter to the Editor” which appeared in TAU 1/96 in reply to that article, and additional research and conversations

with old German Masons over the last few years.

In the years between WW1 and WW2 the blue forget-me-not was a standard symbol used by most charitable organizations in Germany, with a very clear meaning: “Do not forget the poor and the destitute”. It was first

introduced in German Masonry in 1926, well before the Nazi era, at the annual Communication of the Grand Lodge “Zur Sonne”, in Bremen, where it was distributed to all the participants. That was a terrible time in

Germany, economically speaking, further aggravated in 1929 following that year’s “Great Depression”. That economic situation, by the way, contributed a lot to Hitler’s accession to power. Very many people depended on charity, some of which was Masonic. Distributing the forget-me-not at the Grand Lodge Communication was meant to remind German Brethren of the charitable activities of the Grand Lodge.

In 1936 (Hitler was already in control since 1933) the “Winterhilfswerk” (a non- Masonic winter charity drive) held a collection and used and distributed the same symbol, again with its obvious charitable connotation. Some of the Masons who remembered the 1926 Communication –and the forget-me-not– possibly also wore it later as a sign of recognition. We have no evidence of that and its general signification still was charity, but not specifically Masonic charity. Moreover it rapidly became quite impossible to risk wearing anything but Nazi pins. So there were probably only a very few Brethren wearing the forget-me-not, and probably only for a

brief time, until wearing any non-Nazi pins became suspect. There is absolutely no record of the pin, or the flower, ever having been worn during the war (that is after 1939), even less in concentration camps, as the legend also goes.

In 1948 Bro. Theodor Vogel, Master of the Lodge “Zum weißen Gold am Kornberg”, in Selb (then in Western-occupied Germany), remembered the 1926 and 1936 pin, had a few hundred made and started handing it out as a Masonic symbol wherever he went. When Brother Vogel was later elected GM of the Grand Lodge AFuAM of Germany and visited a Grand Masters’ conference in Washington, DC, he distributed it there too, and this was the way it first came to the USA.

Its sudden popularity caused many manufacturers, some Masonic, some not, to pounce upon the occasion and sell the pin all over the world, with a variety of rather contrived and imaginative notes of explanation. The pin is nowadays quite well-known, as are the legends written about its origin, purpose and use… Which does not deter after all from the new message it carries today, through its authors’ imagination if not through rigorous historical record…

And since we are mentioning the forget-me-not, it is any of about 50-odd species of the genus Myosotis, family Boraginaceae, carrying clusters of blue flowers and native to temperate Europe, Asia and North

America.

![]()

“THE BLUE FORGET-ME-NOT” ANOTHER SIDE OF THE STORY

by W.Bro. ALAIN BERNHEIM 33°

In a paper that was published in The Philalethes in February 1997, I contrasted the little-known courage of a small minority of German Masons who opposed the Nazis publicly with the until-recently-ignored cooperative attitude of the great majority of German Freemasons and Grand Lodges toward the Hitler regime in the 1930s.

It was outside the scope of that paper to mention that about 1946 leading German Masons secretly agreed never to mention masonic events from the 1920-1935 period. The first public Declaration of the United Grand Lodge of Germany, issued on 22 January 1949, gave a version of the past which had little in common with factual truth.[i] It asserted that not one single German Mason had taken part in the Nazi crimes, which may have been true. Nevertheless, in 1949, former members of the Nazi party such as Wilhelm Lorenz (a member since 1 July 1936), Hermann Dörner (1 March 1937), Udo Sonanini (1 January 1938), Kurt Hendrikson (1 January 1941), Herbert Kessler (1 May 1941) and Karl Hoede (with the personal authorization of Hitler from 4 August 1942 since he was a Mason from 1920 to July 1933; Hoedes son married Theodor Vogels daughter) already were or became soon prominent Masons under the new German republic. [ii]

In February 1953, German Grand Master Theodor Vogel said before the Grand Masters Conference in Washington : It will therefore be apparent to you all how immensely difficult it was after fifteen years of ban and persecution to found the Lodges again and build them up. It is to the credit of my good friend and brother Ray Denslow, P.G.M., who, together with P.G.M. Dietz, visited Germany on behalf of the Masonic Service Association in 1949, that he in his report After Fifteen Years” described this work with all its difficulties, its troubles, its obstacles…’. [iii] With these words, he was merely acknowledging the fact that his public relations operation had been a success.

In 1945 and in 1949, The Masonic Service Association had sent two delegations headed by Bro. Ray V. Denslow, P.G.M. of Missouri, to Germany. Among the first delegation was Judge (Bro.) George Edward Bushnell, then Grand Lieutenant Commander of the Supreme Council, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction of the U.S.A. Bro. Martin Dietz, P.G.M. of New Jersey, who spoke German fluently, belonged to the second one. The report signed by Denslow and Dietz proves that American delegates received biased and incomplete information. It did not mention once the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Germany or the Supreme Council for Germany, both founded in 1930, the only German Masonic bodies which openly resisted Hitler. Nor did it mention the declarations of Prussian Grand Lodges which openly supported him in 1933 and 1934. It depicted an imaginary German Freemasonry too weak to resist the Nazis and forcibly dissolved in 1933. That information, which reflected the agreement to forget the past, mostly originated in Theodor Vogel. Had the American delegates been fully informed of the attitude of most German Masons in the 1930s, I presume that their report would have been different.

Vogel (1901-1977) was made a Mason in 1926, became Assistant Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of the Sun (Bayreuth) in 1947 and its Grand Master one year later. He certainly tried his best to unite the pre-war German Grand Lodges, partly succeeded, and was elected at the head of the (first) United Grand Lodge (singular) of Germany, 8 October 1948. His success was a partial one only, then the National Grand Lodge (Grosse Landesloge) declined to join Vogels United Grand Lodge and founded a Union of Christian Grand Lodges of Germany of its own which was recognized by the Swedish Grand Lodge in 1953.[iv]

However contemporary relevant speeches and declarations, especially those made by the German Christian Orders – as the three Prussian Grand Lodges chose to rename themselves [v] – were kept secret for a long time. In a paper he read in June 1973 before Quatuor Coronati Lodge in London, Ellic Howe was the first English-speaking Mason to quote from their circular letters issued in 1933. He came to the following conclusion : The position in January 1934, a year after the Nazis came to power, was that the three German Christian Orders had at least survived. In spite of all their protestations of loyalty to the National Socialist regime and its ideology they were tolerated but no more’.[vi] The United Grand Lodge of England prevented the paper from being printed in AQC 86. A typewritten note at the head of the distributed advance copies of Howes paper said : The UGL of England, for reasons best known to its Rulers of the Craft” refused publication to this article. It appeared eventually in AQC 95 (1982).

ALLEN E. ROBERTS’ LETTER AND THE FORGET-ME-NOT PAMPHLET

In 1996, I received a letter from Bro. Allen Roberts, announcing I had been elected a member of the Masonic Brotherhood of the Blue Forget-Me-Not, and explaining: This symbol was born in the face of Nazi persecution of Freemasonry under the Hitler regime. Although the dictator ordered thousands of Freemasons murdered, tortured and incarcerated, those who would not renounce the Craft and its teachings continued to practice Freemasonry in secret. So they might know each other, a little flower was selected as their emblem.’

Together with his letter, Bro. Roberts sent me a pamphlet of twelve unnumbered pages, The Masonic Brotherhood of the Blue Forget-Me-Not. On page [3], a short text of three paragraphs, possibly written by Roberts himself, began thus : As early as 1934, it became evident that Hitler and his Nazi dupes would endeavor to eradicate Freemasonry. The Grossloge zur Sonne (Grand Lodge of the Sun) needed a more subtle symbol than the Square and Compasses to identify its Brethren. An unobtrusive little blue flower, the forget-me-not, was chosen as its Masonic symbol.’ The second paragraph quoted words by David C. Boyd from a paper issued in The Philalethes in April 1987 which is mentioned below. Then followed the prerequisites for becoming a member. Page [4] was devoted to a meeting of the Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons in the Province of Ontario in April 1973 and to the Address on the little blue flower then made by a visitor named Gunter Gall. Pages [5-6] explained who the Founders were, and stated The first awards were made on January 1, 1971. The remaining pages contained the list of Members Awarded The Masonic Brotherhood of the Blue Forget-Me-Not (Masonic Educators and Writers) January 1, 1971 to January 1, 1993.[vii]

I was moved by the distinction, especially since I had been arrested by the Gestapo in Paris when I was twelve. However, since I was somewhat familiar with the history of German Freemasonry between both World Wars, the mention of an emblem worn by German Freemasons under the Hitler regime sounded a bit odd. Many German Freemasons wear nowadays a forget-me-not pin instead of the more conspicuous square and compasses to show that they belong to the Craft. But since when and why ?`I didnt know.

ERNST GEPPERTS POINTS

Two years later, my friend Bro. Pierre Nol sent me the copy of a letter recently written by one of Germanys foremost living historians, Bro. Ernst-G. Geppert. Geppert, who was born in 1918, and has been a Freemason since 1951. Besides numerous papers, he published in 1974 a tremendous piece of scholarship : the first full list of all German lodges since 1737.[viii] His letter was addressed to the Master of a newly-founded German Lodge which had selected the blue forget-me-not as Lodge jewel, and explained why in a printed note. Geppert wrote to the Master correcting the mistakes in the note and closed with the dry remark : You might perhaps at some time choose to adjust your version to the factual one.

Geppert made the following points : [ix]

1. The Grand Lodge zur Sonne (Bayreuth) used to let a pin be made for its yearly meetings and it gave one to each delegate. Those made for the meeting held in Bremen about 1926 represented a forget-me-not, and were manufactured in a factory located in Selb, a small town near Bayreuth. The Brethren from Bayreuth never thought of replacing the Square and Compasses with a forget-me-not.

2. In 1934, the Nazis invented the so-called Winterhilfswerk, which consisted in collecting money on the streets during specific weeks in winter. The money was in fact used for rearmament. Youngsters were requested to participate, and Geppert happened to be one of those who received about one hundred badges, sometimes pins, to be sold at a minimum price. Different ones were chosen each winter and they were worn only during the time of a collection to identify those who had already contributed.

3. By an extraordinary coincidence, the badge used by the Nazis for the collection made in March 1938 happened to be the very forget-me-not pin chosen by the Freemasons in 1926 and it was made by the same factory in Selb. No doubt, comments Geppert, Freemasons who attended the Bremen meeting of 1926 were glad to wear it again twelve years later. However it is out of question that such a pin could have been worn after the March 1938 collection : wearing a mark or a badge which did not originate in the Party was a criminal offence under the Nazi regime.

4. When Grand Master Vogel installed a new Lodge at Selb in 1948, he remembered the story of the pin. Since the factory and the mould still existed, he let a large quantity be made anew and distributed them as a token of friendship whenever he made official visits abroad, especially in the U.S.A., where Geppert accompanied him in 1961.

5. This explains why the blue forget-me-not turned out to be regarded as an official German Masonic emblem after the war. Geppert heard Grand Master Vogel tell the 1938 story while in America, and admits he told it himself. However, writes Geppert, the point made was outwitting the Nazis and their Winterhilfe badge.

6. This also explains why, when American Masons later founded military Lodges in Germany, some of them chose that flower as a Lodges name. Such is the case of Lodge N° 896, Forget me not, in Heilbronn, warranted by the American Canadian Grand Lodge in 1965.

THE TAU PAPER BY KLAUS MILLER AND THE ENGLISH’ DOCUMENT

In volume II. (1995) of TAU, the biannual publication of the German Quatuor Coronati Lodge of Research, I discovered a short paper written by the Master of the Lodge, Bro. Klaus Miller, stating that each newly-admitted Mason within the Grand Lodge of British Freemasons in Germany received a forget-me-not pin together with a printed story of the emblem, whereas the American Canadian Grand Lodge gave such a pin to Master Masons when they were raised. The paper included the facsimile of a text entitled The True Story Behind This Beloved Emblem of the Craft in Germany’ which ended thus : In most Lodges, the Forget-Me-Not is presented to new Master Masons, at which time its history is briefly explained. Klaus Miller did not specify which Masonic body issued that text, though he introduced it as the English text.

HAROLD DAVIDSONS DOCUMENTS

I asked Harold Davidson, Librarian of The Philalethes Society, to send me any paper or document he might be aware of related to the forget-me-not story. He did so at once, and I wish to express my gratitude for his brotherly help.

One document Harold sent me was the Xerox copy of an undated Presentation card issued by the American Canadian Grand Lodge, AF&AM, within the United Grand Lodges of Germany’ entitled The Forget-Me-Not. The Story Behind This Beloved Emblem Of The Craft In Germany. It mentions that a forget-me-not pin is presented to newly-made Masons in most Lodges of that Jurisdiction (accordingly, one of Klaus Millers statements appears likely wrong).

Harold also sent me a paper written by David G. Boyd, MPS, Das Vergissmeinnicht, which appeared in The Philalethes in April 1987.[x] The author relied on Ellic Howes paper for general information about German Freemasonry and the Nazis. For the Masonic origin of the blue forget-me-not, Bro. Boyds authority was a speech made by a Bro. Gunter Gall [xi] at the Royal Arch Grand Chapter Meeting of April 1973, quoted in the pamphlet Allen Roberts sent to me :

Throughout the entire Nazi era, a little blue flower in a lapel marked a brother. In the concentration camps and in the cities, a little blue forget-me-not distinguished the lapels of those who refused to allow the Light of Masonry to be extinguished. When in 1947, the Grand Lodge of the Sun was reopened in Bayreuth, a little blue pin, the shape of a forget me not was proposed and adopted as the official emblem of the first Annual Convention of those who had survived the bitter years of semi-darkness, bringing the Light of Masonry once again into the Temples. A year later, at the first Annual Convention of the United Grand Lodges of Germany, A.F. and A.M., the pin was adopted as an official Masonic emblem honouring those valiant brethren who carried on their work under adverse conditions. Thus did a simple little flower blossom forth into a meaningful emblem of the Fraternity, becoming perhaps the most widely worn pin among Freemasons in Germany.’

Bro. Boyds comment to the above : it is unlikely that it was often worn even in the dark days of the Third Reich… it is unlikely such a symbol would have long remained unknown, unless it was employed most sparingly.

ALLEN E. ROBERTS’ WRITINGS

In his famous Seekers of Truth (1988), Allen E. Roberts wrote But not all German Freemasons submitted the wiles of Adolf Hitler and his regime. Some of the more dedicated Master Masons went underground. For identification they wore a little flower called a blue forget-me-not.” This later became a national Masonic symbol in Germany.’ [xii]

Two years later in The Northern Light, he sounded a bit more cautious : Myth : Persecuted German Freemasons wore a blue forget-me-not for identification after 1934. Fact : This has been accepted as fact by most scholars but still questioned by a few. Cyril Batham of England, for instance, disputes the date. He claims it was adopted in the 1920s as a badge of friendship. His report and previous accounts agree that it was the Grossloge zur sonne (Grand Lodge of the Sun) that developed the symbol. Earlier reports say this Grand Lodge designed it as a means of evading the Gestapo ; Batham claims it was simply an emblem selected because the Square and Compasses wasnt worn by Freemasons. Most important, though, the early accounts and Batham do agree the blue forget-me-not was worn throughout the Nazi terror. This emblem was also chosen to honor Masonic writers and educators through The Masonic Brotherhood of the Blue Forget-Me-Not. This group was organized in 1972.[xiii]

CONCLUSION

Nobody ever said seriously I have just invented a tradition. A clever person would like his friends to believe that the legend which had just come to his mind was an old one which, for some unknown reason, became forgotten, extinct, or both. He would rather say: I have rediscovered a very old tradition. In October 1987 Bro. Boyd wrote : The more you dig into any facet of Freemasonry, the more you inevitably find. Unfortunately, it often happens that what you find may be difficult to prove or downright untrue. The story of the forget-me-not is just one such case. [xiv] How right he was !

What I was able to find about the Masonic tradition surrounding the blue forget-me-not amounts to very little. It is true that the flower was used by some German Masons about 1926, and it appears likely that in March 1938 some of them did wear it again as a Nazi badge, even though by an extraordinary coincidence, it had been chosen as a Masonic emblem twelve years earlier. It is likely not true that it was ever worn after March 1938 as a secret mean of recognition. However, even if many German Masons (together with the great majority of German citizens of that time) never objected to the Nazi politics and went so far as to support Hitler, some were brave enough to fight him openly. My estimation, based on the membership of all the then existing German Lodges, is that they amounted to 1 or 2%. Out of the 174 Lodges which participated in the creation of the first United Grand Lodge of Germany, five only belonged to the Symbolical Grand Lodge of 1930, the only German Grand Lodge which resisted Hitler.

For human and political reasons as well, those Masons who thought it their duty to rebuild German Freemasonry once the War was over could hardly tell the whole truth to their foreign brethren. I personally believe they might have told the story of those dark years in a different way, but I am ready to admit that it is probably easier to say so in 2000 than in the 1950s.

Accordingly a legend was born. Not the legend of the forget-me-not, but that of a German Freemasonry too weak to resist, banned as soon as Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, wearing a badge on the streets and – of all things ! – in concentration camps. That legend was likely born as the result of an unconscious effort to inhibit the past as well as a conscious maneuver. It was believed not only because it was the logical thing to do, but also because it was reassuring to imagine Freemasons acting according to their ideals, fighting for freedom and defending it.

Lets keep it at that and let us admit to the Masonic Brotherhood of the blue Forget-Me-Not those who, as Allen E. Roberts put it once, continue the battle.

NOTES

[i] See La Franc-Maconnerie allemande au 20e sicle, an address I gave at the Free University of Brussels, 8 May 1998, published in Ars Macionica (Brussels) 8 (1998): 17-40. See also the recent thesis of a young German historian, Ralf Melzer, who is not a Mason: Konflikt und Anpassung. Freimaurerei in der Weimarer Republik und im Dritten Reich” (1999, Braumller, Wien).

[ii] Names and dates from declassified documents filed in Bundesarchiv, Abt. III Aussenstelle Berlin Zehlendorf (former Berlin Documentation Center).

[iii] Conference of Grand Masters of Masons in North America, Washington 1953 : 86.

[iv] After recognizing the United Grand Lodge of Germany in December 1956, the United Grand Lodge of England invited German and Scandinavian delegates to a Conference in London in June 1957. Under considerable pressure, the National Grand Lodge finally agreed to become a party to the present United Grand Lodges (plural) of Germany, founded in April 1958.

[v] In April 1933, the three Prussian Grand Lodges had changed their original names into those of National Christian Orders. See Bernheim, ‘German Freemasonry and its Attitudes toward the Nazi Regime’, The Philalethes, February 1997: 20-21.

[vi] AQC 95 (1982) : 32. Italics added by the present writer.

[vii] Alphabetical list of 298 Members of the Brotherhood on January 1, 1993. Facing each name was a number. The four members numbered 000’ were likely the Founders : Walter M. Callaway Jr., Conrad Hahn, Allen E. Roberts and John Black Vrooman. No. 001 was John M. Sherman.

[viii] Die Freimaurer-Logen Deutschlands und deren Grosslogen 1737-1972 (Quatuor Coronati Bayreuth, Hamburg 1974). Second revised edition, Karl Heinz Francke and Dr. Ernst-Gnther Geppert, Die Freimaurer-Logen Deutschlands und deren Grosslogen 1737-1985 (Hamburg 1988).

[ix] Summary of information provided in a note by Geppert, printed in TAU I. 1996: 110, and in a letter he sent me on 15 February 1999.

[x] David G. Boyd is described by Allen E. Roberts as a lieutenant colonel stationed at Heidelberg, Germany, and Master of Alt Heidelberg Lodge No. 821 in 1987’ (Seekers of Truth, p. 22). He is listed as such in the Jahrbuch der VGLvD for 1988. That Lodge which belonged to the American Canadian Grand Lodge in Germany isnt active any more.

[xi] Gunter Gall, described as Grand High Priest of Royal Arch Masons of Germany in the pamphlet, was Grand Master of the American Canadian Grand Lodge in Germany 1975-76. This Grand Lodge adhered to the Magna Carta and became one of the five United Grand Lodges of Germany, 23 October 1970. It was under its authority that Lodge N° 896, Forget-me-not, mentioned by Bro. Geppert, was warranted 1965 in Heilbronn. Heilbronn is about fifty miles away from Heidelberg.

[xii] Seekers of Truth (1988) : 11. Pages 204-5, Roberts quotes at length the Boyd paper from April 1987 and a further one from October 1987, both published in The Philalethes.

[xiii] Allen E. Roberts, Masonic Myths, The Northern Light (February 1990).

[xiv] The Philalethes, October 1987. That second paper was entitled Das Vergissmeinnicht, under-title The Myths.

Resource: http://web.archive.org/web/20040209003702/http://users.libero.it/fjit.bvg/bernheim3.html

According to the United Grand Lodge of England, the Grand Lodges of the United States, Canada, Australia etc, the only Freemasons in Germany were the ‘Old Prussian Grand Lodges’ – the Lodges which forbid Jews membership. The Grand Lodges which permitted Jews membership were known collectively as ‘Humanitarian’ Lodges and were considered ‘clandestine’ and not Freemasons by the arbitors of ‘Regular’ Masonry. It was these ‘Humanitarian’ Grand Lodges which Hitler outlawed in 1933. The ‘Regular’ Grand Lodge Grand Master’s all sent letters of congratulations and loyalty to Hitler and were allowed to continue operating under the cover name of ‘The Frederick the Great Christian Association’. Frederick the Great was of course the founder of ‘regular’ Freemasonry in Germany and was Hitlers personal hero. You won’t find these facts on any Masonic website however, as Freemasonry’s current gambit is to continue to propagate the ‘official’ lie of the Blue Forget Me Not Pin in an effort or conceal ‘Regular’ Freemasonry’s involvement and support of Hitler and National Socialism. These little known facts give further weight to those historians and writers who believe Deputy Furher Rudolf Hess met the Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England, the Duke of Kent, following Hess’s strange solo flight.

German Freemasonry’s Attitude Toward The Nazi Regime

Alain Bernbeim, MPS

Philaltethes Magazine

February 1997

Germany’s Grand Lodges Up To 1930

At the beginning of 1930, Germany comprised some 75,000 Masons and nine regular Grand Lodges, the numerical importance of which was very different.

Table 1- Masonic Membership In Germany 1930 -1932

Grand Lodges………….Founded……..Lodges…………..Membership

……………………………….1930…..1932……..1930……1932

‘Old Prussian’

Three Globes……………1744…….177……183……..21,300….21,300

Grand Land Lodge………..1770…….179……180……..20,400….20,400

Royal York of Friendship…1798…….108……109……..11,400….11,000

‘Humanitartian’

Hamburg………………..1811…….54…….54………5,000…..5,000

Bayreuth……………….1811…….45…….42………4,000…..3,800

Dresden………………..1811…….45…….46………7,300…..6,900

Franklurt………………1823…….26…….26………3,200…..3,000

Darrnstadt……………..1846…….10…….10………900…….900

Leipzig………………..1924…… 10…….10………1,900…..1,900

Othcrs ………………………….

Rising Sun……………..1907……. 2,000

Symbolic Grand Lodge…….1930…….8……..13 800

About two-thirds of the brethren belonged to the three oldest, always Christian-oriented and at that time strongly nationalistic Grand Lodges founded in the 18th century which were called ‘Old Prussian’ because they were founded and had their seats in Berlin. They never initiated ‘non christians’, that is, Jews. Along the l9th century, five more German Grand Lodges were founded and a further one in 1924. They were called ‘humanitarian’ and initiated men of any religious denomination.

Table 2 – German Grand Lodge and ‘non-Christians’ (S)

Grand Lodges……..Formal decision………Visit of……….Initiation of

………………..to initiate only……..non-Christians….non-Christians

………………..Christians:………….possible:………possible:

‘Old Prussian’

Three Globes………….1763…………….1849………….impossible

Grand Land Lodge………1770…………….1857………….impossible

Royal York of Friendship.1815…………….1854………….impossible(*)

‘Humanitarian’

Hamburg………………never……………1811………….1841

Bayreuth……………..1833…………….1847………….1847

Dresden………………1831…………….before 1845……

Frankfurt/Main………..1810…………….1838………….1844

Darrnstadt……………1846…………….1873………….1873

In 1922, the Old Prussian Grand Lodges decided to withdraw from the German Grand Lodgs’ Alliance founded in 1872, explaining: ‘There is a border which strongly dfferentiates humanitarian from Old Prussian national Freemasonry. We, the three Old Prussian Grand Lodges refuse to take part in the general humanitarian fraternization movement between people in the world.’ . (Steffens, p. 332)

Some brethren believe that there was only one type of German Freemasonry which was indifferently persecuted by Hitler. In fact, several masonic spiritual families existed side by side in Germany, which reacted and were treated differently by the Nazis.

In the March 1933 issue, the last one to be printed in Germany, the Symbolic Grand Lodge announced that on March 28th, it had resolved to become dormant. That issue also included the text of a resolution in support of Hitler, adopted toward the end of March by the National Mother-Lodge The Three Globes. It was followed by an article from the Nationale Zeitung, Essen, dated March 30, 1933, declaring The Grand Lodge of Saxony [at Dresden] sent a telegram expressing its faithful support to Dr. Goebbels The three [Berlin] Grand Lodges even sent a congratulatory address to the Reich chancellor Hitler.

![]()

Other sources to check:

The Philalethes magazine

Aug 1969, A Mason Visits in Europe

Dec. 1970, Forget Me Not

Feb. 1978, Callaway

DEc. 1978, Third Reich

June 1984, President’s Corner

Feb. 1986, Vrooman

Apr. 1987, Das …

Oct. 1987, Das …

Apr. 1988, Case

June, 1988, Roberts

Feb. 1990, Smith

Apr. 1990, p. 11

Apr. 1990, p. 24

Aug. 1990, McGaughey

Feb. 1992, Marsengill

Apr. 1992, p. 41

June 1993, Smith

Aug. 1994, French

Feb. 1996, p. 10

Seekers of Truth, pages 11, 204, 205

Paul M. Bessel